An Old Tool Creating New Dangers

Throughout much of the modern era, limiting or disrupting the flow of energy was a highly effective tool of global power. In 1923, Admiral Reginald Bacon of the Royal Navy declared that the United Kingdom’s oil blockade of Germany in World War I was the powerful economic weapon to which “the ultimate collapse of that nation and her armies was mainly due.” A generation later, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin attributed the Allied victory over Nazi Germany to the Red Army’s success in denying Hitler access to oilfields in the Caucasus. Then there was the 1973 Arab oil embargo, which caused a nearly 300 percent rise in the price of gas in the United States and miles-long lines of cars at gas stations, an experience that has remained seared in national memory.

For much of the next 50 years, however, the use of energy as a coercive tool of statecraft largely subsided. The disastrous effects of the Arab oil embargo on the global economy led both producer and consumer countries to think differently. Over the years that followed, consumer countries sought to make their energy flows more resilient and build stronger and more transparent international markets, while producers reined in their propensity to use their energy prowess as a geopolitical cudgel. The end of the Cold War and the subsequent acceleration of globalization boosted reforms that further integrated oil markets and diversified energy supplies. In the early years of the twenty-first century, even soaring prices and fears about peak oil—the notion that global oil production was close to its maximum and would soon begin an inexorable decline—proved short-lived as the American shale-drilling revolution brought unprecedented new volumes of oil to the market. Oil prices continued to fluctuate during major conflicts such as the first Gulf War and the Libyan civil war and global crises such as the Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic. But throughout this era, consumers, particularly in advanced economies, were increasingly confident that markets would deliver the energy they needed. Over time, many countries were lulled into complacency about energy security.

Today, that complacency has been upended. Following its 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Russia inflicted enormous economic pain on Europe by slashing its natural gas deliveries to the continent and sparking an energy crisis with global reverberations. As part of its larger trade confrontation with the United States, China has periodically restricted the export of key critical minerals and rare-earth elements—parts of a supply chain that is crucial to semiconductors, military applications, batteries, and renewable energy. The United States itself has also politicized the flow of energy, demanding that Europe buy more American energy to gain relief from threatened trade tariffs. Even countries such as Canada have entered the fray, with Ontario imposing a surcharge on electricity exports to the United States in retaliation for President Donald Trump’s sweeping new tariffs on Canadian goods. As producers wield the energy weapon that was largely sheathed for the last several decades, the United States and others are also rebrandishing their influence over the production and purchase of energy, as seen in Washington’s recent moves to prohibit most American oil and gas firms from operating in Venezuela and to consider steeper sanctions on countries buying Russian and Iranian oil exports.

In a world that had grown accustomed to relatively stable and secure energy markets and was under the illusion that the clean energy transition would neutralize energy geopolitics, the return of the energy weapon has caught many by surprise. Yet this trend is unlikely to end soon for two broad reasons. First, at a time of renewed great-power competition and economic fragmentation, energy has once again become an attractive instrument of geoeconomic coercion. Second, significant developments within the energy sector are creating new opportunities for weaponization even as they mitigate some others.

Fortunately, there are a variety of policy tools to address these threats—most of which are compatible with and enhanced by the clean energy transition. Indeed, by making a faster shift toward zero-carbon sources of energy, countries can eventually build a strong form of resilience against energy weaponization, especially if such a push is coupled with efforts to diversify clean energy supply chains. To mount an effective response, however, policymakers need to recognize the forces driving weaponization and the broader risks they pose to national security and the global economy. With more countries threatening to make coercive use of more different kinds of energy flows, the world could be at the dawn of a new age of energy weaponization.

Global Entry

Throughout much of the twentieth century, controlling the flow of oil was considered an essential component of foreign policy and military strategy. Countries endowed with energy riches used those resources as a means to achieve objectives outside the energy realm. And those whose geology was lacking often saw the need for energy as an end—a reason to harness military, economic, and diplomatic power in its pursuit. For decades after oil became the dominant global energy source, producers were in a strong position. By the 1970s, oil supplied about half the world’s energy needs. And since it was typically sold in long-term contracts at administered prices set by a small number of governments, producers could assert control over both supply and price. With such levers, countries with major oil reserves could seek to sway international policies in the realm of politics. In 1973, after the outbreak of war between Israel and its neighbors, the Arab members of OPEC restricted oil exports to countries supporting Israel and incrementally curtailed global supply to compel the United States and other Western powers to cease support for Israel and force Israel to withdraw from captured territories. The move triggered what one adviser to U.S. President Richard Nixon called an “energy Pearl Harbor.” By the end of the year, the price of a barrel of oil, which three years earlier had been $1.80, reached $11.65—the equivalent of more than $80 today.

Yet the Arab oil embargo proved to be a turning point. It produced a wide array of negative consequences, including stagflation in advanced economies and a massive debt burden in the developing world. It also failed to compel the West to abandon Israel. It did, however, drive many countries to launch an intense effort to conserve energy, boost oil production outside OPEC, reduce imports, and prioritize energy security. In 1974, advanced economies came together to form the International Energy Agency (IEA), the centerpiece of which was an agreement to build strategic oil reserves for coordinated release in times of emergency. As it became clear that price controls and energy rationing had exacerbated the effects of the embargo, U.S. leaders and policymakers also realized that more flexible, integrated, and well-functioning global oil markets could disperse the impact of supply disruptions—spurring efforts to liberalize the oil trade. In the early 1980s, governments sought to improve the quality and transparency of energy data and to deregulate oil pricing, helping pave the way for the inclusion of crude oil futures on the NYMEX commodity futures exchange. Thereafter, oil went from being largely traded in long-term contracts at fixed prices—an approach that made it difficult for buyers to find alternative sources of supply during disruptions and thus vulnerable to producer pressures—to the most traded commodity in the world.

Although the process was slower and looked very different, natural gas markets were also becoming more globally integrated. After the first shipment of liquefied natural gas sailed from Louisiana to the United Kingdom in 1959, successive waves of supply growth—including from Algeria in the 1980s, Qatar in the 1990s, and the United States in the last decade—transformed the natural gas trade. They contributed to a more integrated and flexible LNG market that could better respond to changes in supply and demand than fixed gas pipelines, since tankers can deliver to many destinations and are easily redirected. Starting in the 1980s, despite Europe’s growing dependence on Soviet—and later Russian—gas, policymakers and buyers became more confident that competitive markets and mutual dependence would shield the continent from geopolitical vulnerability. Indeed, for much of the Cold War, many leaders perceived the energy trade between western Europe and the Soviet Union as a moderating influence on the larger geopolitical rivalry.

The end of the Cold War only accelerated these positive trends. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 paved the way for the 1994 Energy Charter Treaty, which created a multilateral legal framework for energy cooperation. Initially intended to provide a legal structure for energy trade, transit, and investment between western Europe and post-Soviet states, the treaty later expanded to incorporate countries from other regions. Investments began flowing into Russia and former Soviet republics from Western energy companies such as Exxon, BP, and Total, further increasing interdependence and the breadth and depth of global markets. In this new era of cooperation, the United States and Russia created a Megatons to Megawatts program, in which the United States purchased excess highly enriched uranium from Russia’s defense sector and turned it into low-enriched uranium for civilian reactors; for years, policymakers seemed unfazed that the United States was dependent on Russian fuel to operate its nuclear power plants.

The integration of global energy markets was given a huge boost by China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001. To fuel its staggering industrial and manufacturing expansion over the decade that followed, China had to quadruple its oil imports, forcing it to rely heavily on the markets of the Middle East and Central Asia. Over time, Beijing moved away from a “going out” strategy that focused on physical control over energy resources in Africa and beyond to an approach that sought to ensure access to energy from a diverse group of suppliers. Later, through its Belt and Road Initiative, the Chinese government financed pipelines, ports, refineries, and power plants overseas, investing in a network that could help it obtain a consistent supply of energy from multiple points around the world.

As economic relations became more globalized and energy markets became more interconnected, exporters largely set aside the energy weapon. Certainly, there were notable exceptions, as when Russia cut off gas exports to Ukraine in 2006 and 2009. Yet the ensuing European debate over whether the cuts were commercial or political in nature weakened the collective European response to coercion. At the time, most producers seemed to recognize that well-integrated global energy markets limited the impact of withholding or denying energy deliveries to a particular country or region—making calculations about embargoes unattractive. As fiscal budgets ballooned in the Gulf and other OPEC countries, producers were reluctant to take action that could jeopardize their revenue streams, and the threat of another oil embargo by the cartel faded. The net result was that by the early years of this century, there was a general sense among advanced economies that energy security had improved significantly since the 1970s, even as reliance on oil imports continued to grow.

To be sure, energy weaponization did not entirely go away during this era of relative stability, although the sort exercised in the decades after the Cold War was of a different variety. Whereas the globalizing economy and integrated markets made trade sanctions on oil producers less effective, economic interdependence and the dominance of the U.S. dollar made the financial system ripe for weaponization. Consumer countries, particularly the United States, politicized their consumption and deployed financial sanctions against some of the world’s largest oil producers, such as Iran. Energy thus remained a means for advancing foreign policy in this surprising way.

Power Play

In the last several years, the circumstances that set the stage for this extraordinary period of energy cooperation have begun to shift. Perhaps most important, by 2020, the era of closer cooperation among great powers, unfettered trade, and faith in markets was coming to an end. The integration of global markets that had been central to the energy security of so many countries was no longer assured; shifting geopolitical forces were creating economic fragmentation, and governments were beginning to intervene in private enterprise in more far-reaching ways. Major powers are now pivoting toward state capitalism, using trade restrictions and industrial policy to achieve economic and national security aims. In the United States, this shift began during Trump’s first term, continued under the Biden administration, and has expanded further under the second Trump administration, with the government using tariffs as a form of economic coercion in far more aggressive ways. China, which has long engaged in state capitalism, is both pulling back from global markets in many commodities and honing its ability to use sanctions and other state interventions to advance its interests. In this increasingly uncertain geoeconomic environment, countries in Europe and other parts of Asia are finding it harder to assume that markets alone will deliver the energy supplies they need.

Paradoxically, perhaps, the pullback from the integrated global markets that have long helped stabilize energy flows has been partly driven by policymakers’ growing concerns about energy security. In many countries, escalating geopolitical threats, great-power rivalry, high energy bills, risks of supply shortfalls caused by underinvestment in oil and gas, competition for leadership in power-hungry artificial intelligence, and worsening climate impacts have all contributed to a sense that energy security is on the line. Rather than leaning in to global markets, governments may be more inclined to reduce their energy trade and curb their exposure to volatile international forces. Consumer countries increasingly seek to produce more domestic energy and import less, and producer countries may be tempted to curb exports to prioritize their own needs. In early 2025, Norway’s two governing parties pledged to cut power exports to Europe amid concerns about soaring electricity prices at home. Similar pressures may soon arise in the United States. Voters confronting higher utility prices could pressure the government to restrict the country’s burgeoning exports of natural gas in the belief that doing so will lower their bills. In fact, any such moves could undermine the very integration that has helped tame energy weaponization in recent decades.

The rise in clean energy has become a double-edged sword.

Alongside a fragmenting global economy, changes in the energy landscape will encourage renewed use of the energy weapon, even if other developments will cut the other way. Take the oil sector, in which two of the main conditions for past weaponization could reemerge in the years ahead: the tightening of markets and the concentration of supply. Discussions about the implications of global oil demand peaking are gradually being replaced by questions about the consequences of the shale oil boom coming to an end. In September 2025, the oil giant BP acknowledged that oil demand, which it had previously forecast would peak this year, will continue climbing for the rest of the decade. According to a report published by Bloomberg, in a draft of the IEA’s forthcoming 2025 World Energy Outlook, the agency presents a scenario based on current policy alongside one reflecting policies and measures that have been formally announced or are under development. In previous IEA reports, the latter scenario projected global oil demand to peak by the end of this decade; in the draft, the former scenario shows it continuing to grow through 2050. Meanwhile, oil executives and analysts are becoming skeptical that U.S. shale oil production, which met most of the growth in global demand over the last decade, will continue to rise. The U.S. Energy Information Administration has projected that U.S. oil production will decline next year. Major oil companies have also scaled back exploration efforts worldwide, with investment in upstream oil and gas projected to fall in 2025 to its lowest level since the pandemic. As more of today’s existing production capacity is called on to meet rising demand, the amount of spare capacity in the global system will shrink, leaving less of a buffer to cope with price shocks. As a result, the oil market may tighten significantly toward the end of this decade, creating more chances for countries to target the oil supply—through infrastructure attacks, export restrictions, sanctions, or other steps—in ways that inflict economic pain.

In addition, the renewed concentration of supply in the hands of fewer countries will exacerbate the risk of coercion. By 1985, OPEC’s share of the world’s oil production had fallen from about half before the Arab oil embargo to just 27 percent, as huge volumes of non-OPEC oil came to market from the North Sea and other areas. But with the U.S. shale boom slowing and other non-OPEC producers experiencing only modest supply growth, the IEA now projects that the cartel’s share of the global market will rise again to at least 40 percent by 2050, a level not seen since the 1970s. If demand continues to be strong, this concentration of supply will make OPEC countries even more geopolitically influential.

The global gas market may also soon experience changes, including further concentration, that make politicization more likely. It is true that over recent decades, the rise of liquefied natural gas and the emergence of a more globally integrated gas market have greatly reduced opportunities for coercion. When Russia cut off most of its pipeline gas exports to Europe in 2022, for instance, European countries were able to cushion the loss by securing supplies of globally traded LNG, albeit at much higher prices. Nonetheless, shifting dynamics in global gas markets suggest that new dangers may lie ahead. In the coming years, supplies will be more concentrated among a handful of producers, even if Russia’s plan to triple its LNG export capacity by 2030 does not materialize. The sharp growth in LNG exports from Qatar and the United States—in combination with growing European and Asian dependence on LNG—means that more gas will travel through the Strait of Hormuz and from the U.S. Gulf Coast, creating new geopolitical targets. Moreover, although the rise of the United States as an LNG superpower was once seen as a salve for geopolitical risk, the Trump administration’s use of economic coercion against allies and adversaries has stirred fear among energy importers that the United States may no longer be a reliable, apolitical supplier.

Meanwhile, the rise in clean energy across the globe has become a double-edged sword when it comes to energy security. Increases in wind, solar, and other new sources of energy have helped the world meet burgeoning demand and have diversified the energy mix of large economies, most notably China. But the clean energy transition could introduce new threats, particularly in relation to the rush toward electrification. Spurred by the massive power needs of the data centers that enable artificial intelligence, the growing use of air-conditioning and electric vehicles, and rising industrial activity around the world, electricity’s share of global energy use will rise from 20 percent today to 25 percent in 2035, according to IEA projections.

To some extent, a more electrified world will help reduce the risk of energy coercion, since most countries can produce much of their electricity from domestic sources. But wherever electricity crosses borders, electrification carries new risks. Importers of electricity are even more vulnerable than oil importers, as these countries tend to have few if any alternative sources of supply, and electricity is far more difficult to hold in strategic stockpiles than oil. Today, only a tiny fraction of global electricity supply is traded across borders. Yet plans to develop many more long-distance transmission lines to connect countries in many parts of the world, including in the Asia Pacific as well as Europe and North Africa, could make this concern more potent.

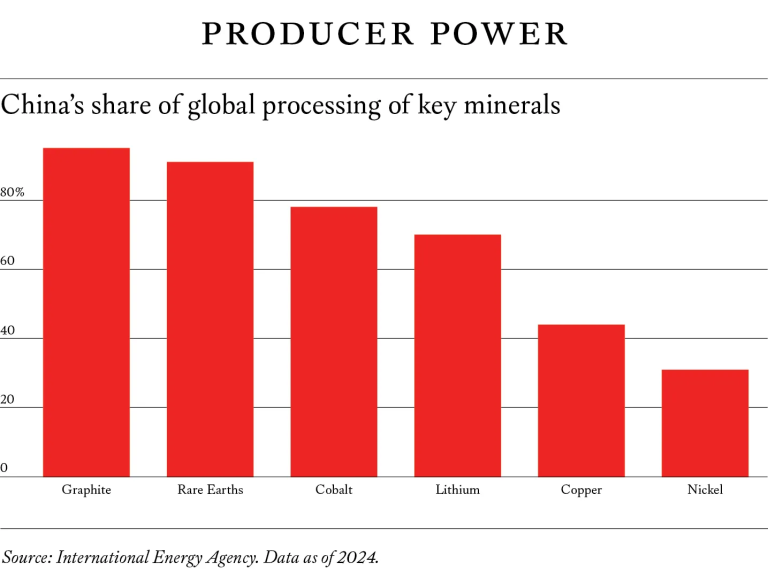

Of greater concern on a global level is the dominant role that China and a few other countries play in supplying the inputs needed for widespread electrification. Transmission lines, solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries for cars, trucks, and the electric grid all depend on critical minerals, such as copper, nickel, lithium, graphite, and rare earths. Demand for these minerals is projected to surge in the coming years, with lithium use increasing fivefold and graphite and nickel use doubling by 2040. China is the top producer of 19 of the 20 critical minerals assessed by the IEA to be key to the energy sector, and it accounts for more than 70 percent of global refining capacity for these metals and minerals. The global minerals supply is also dominated by a few other countries, such as Indonesia for nickel, the Democratic Republic of the Congo for cobalt, and Russia for enriched uranium. In fact, the mining of certain metals and minerals is even more concentrated than the production of oil. According to the IEA, when the leading producer of each of the key battery metals and rare earths is excluded, other remaining suppliers will, on average, be able to meet only half the remaining global demand in 2035.

Spurred by the clean energy transition, energy flows are also shifting to include not only the transport of commodities—oil, gas, coal, or critical minerals—but also the trade of manufactured goods such as solar panels, wind turbines, batteries, and electrolyzers. The production of these goods is also firmly dominated by China, which now accounts for more than 80 percent of solar manufacturing capacity and nearly as much for key parts of the wind supply chain. In batteries, China’s role is even greater, accounting for more than 85 percent of all steps of the battery value chain and up to 95 percent for anodes—the part of the battery that stores energy when it is charging. All of which raises questions about whether these goods could become hostages to politics or conflict in the future.

Real-world developments give us reason to take such concerns seriously. In 2010, during a standoff over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea, Beijing temporarily suspended the export of rare-earth minerals to Japan, causing significant concern in Japan’s high-tech industries. In late 2024 and early 2025, amid tensions with the United States over the flow of technology, China restricted the export of graphite, certain critical minerals, and rare earths, leading to price spikes and supply chain disruptions that put significant constraints on U.S. manufacturers. Ford Motor Company, for instance, had to temporarily idle some of its American plants because of shortages of Chinese-supplied rare-earth magnets.

The potential for Chinese weaponization of clean energy, given Beijing’s production dominance in minerals as well as in solar panels and batteries, is a key element of this new age of intense geopolitical rivalry. Particularly in light of future scenarios in which Washington and Beijing are at odds over the future of Taiwan, policymakers must consider China’s ability to flood the market for critical minerals, rare earths, or clean energy products and undercut the competition, or to restrict exports to deter or blunt Western responses and peel off U.S. allies that are economically dependent on Chinese inputs. Such a move could create price spikes and shortages, not just in energy supply chains but also in materials needed for defense readiness and weapons production.

Concerns over the weaponization of electricity also extend to energy infrastructure. In 2024, the FBI warned that state-sponsored Chinese hackers had penetrated critical networks across the United States in what then FBI director Christopher Wray characterized as a “broad and unrelenting” threat. Power grids can be an especially attractive target for weaponization. Given that electricity is the key energy input in the highest-value-added sectors, such as advanced manufacturing and artificial intelligence, electricity disruptions can cause outsize economic harm. Greater electrification, renewables, and extreme heating and cooling needs will require grids to handle more frequent periods of peak electricity demand, creating more opportunities to attack networks at moments of maximum strain and vulnerability.

More Efficiency, More Security

With the return of the energy weapon, policymakers will need to think differently about energy policy, as well as foreign policy and national security. Given the transformative shifts in the energy landscape, the retreat of globalization, and the return of great-power rivalry, the opportunities for countries to use energy as a means to gain influence or achieve foreign policy goals are intensifying and go well beyond oil. The old antidote of integrating into well-functioning, interconnected global markets still provides benefits, but it may offer less protection as markets themselves fragment and energy is weaponized in new ways. Policymakers and others will need to find ways of protecting citizens and businesses from the volatility that energy weaponization will undoubtedly bring.

A few obvious prescriptions, applicable to all countries, are to reduce exposure to volatile energy supplies, build up buffers against potential shocks, and increase energy efficiency. Some countries, based on their geology, may also have the option of boosting domestic supplies of oil and gas to curb their reliance on imported energy. In the United States, for example, policymakers may be tempted to seek greater or even total energy self-sufficiency to limit the threat of weaponization. But energy independence in this sense is a myth. Today, the United States produces more energy than it consumes, but it still imports and exports significant amounts of oil and is therefore enmeshed in global markets and susceptible to any volatility in them. In a more weaponized world, true energy security will require not just producing more oil or gas but also and especially consuming less.

Leaders of countries in Europe or East Asia that have long depended on oil and gas imports—even more so than the United States—can protect themselves from volatile markets by reducing their energy trade, nearly all of which today is in fossil fuels. Although “replacing” some of these imports can be accomplished by increasing efficiency, paring down most will require more intense electrification with energy that is generated domestically, for instance from solar, wind, nuclear, or geothermal sources. (For some countries, for example in South Asia, it can also mean domestically produced coal.) Given the risks posed by clean energy supply chains, one might ask how much protection such a shift provides. Former U.S. Senator Joe Manchin has lamented the dilemma of trying to “replace one unreliable foreign supply chain with another.”

But the risks posed by the oil and gas sectors are of a different order than those of the clean energy sector. The possibility that China could weaponize clean energy supply chains is real, bringing with it the potential to limit the ability of many countries to deploy new EVs, solar panels, or battery storage for the grid. Unlike with oil or gas, however, such tactics would not jeopardize the flow of energy itself. China’s weaponization of supply chain concentration would not quickly cause lights to go out, cars to sit idle, or homes to freeze. Instead, it would lead to higher costs and delays for products that produce and store energy. And although such supply chain risks could have significant economic impacts, these would be easier for most countries to address over time. Unlike the production of fossil fuels, which depends on the good fortune of geology, manufacturing capacity can be ramped up in most places. For those reasons, on energy security grounds alone, the United States should reconsider its current retreat from policies that seek to modernize and expand the electric grid and to develop more domestic clean energy generation and manufacturing.

Using clean energy to mitigate the weaponization of fossil fuel markets makes sense for other reasons, as well. By offering subsidies, eliminating excessive regulation, and streamlining permit processes, mineral-rich countries can encourage more domestic production and investment in manufacturing, mining, and grid construction. But all consumer countries can build manufacturing capacity such as mineral refining and processing. They can also reduce their dependence on Chinese-dominated supply chains by investing in energy projects in a more diverse set of places, such as the mining, refining, and processing of critical minerals in Africa and Latin America. Governments can also make their national energy infrastructure more resilient against attacks by hardening power grids, managing periods of peak demand more efficiently, and implementing better protections against cybersecurity threats. Finally, to cushion against future shocks, policymakers will need to create and expand emergency stockpiles, such as for certain critical minerals and natural gas, along the lines of what the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve has done for oil.

Beyond such direct policy action, decision-makers will need to think more creatively about state intervention in the energy sector. Already, the quest for energy security in today’s fractious environment is leading governments to seek solutions to problems that would have been left to the market to resolve in an age of greater international cooperation. In some cases, these interventions, such as a recent equity investment by the Trump administration in a domestic rare-earth company, will make sense and even be necessary to make the United States and other countries less vulnerable to energy coercion. Such moves toward state capitalism, however, introduce significant risks and require guardrails to prevent political or ideological interference with corporate decision-making.

The All-In Defense

The idea that a new era of energy weaponization has begun may seem counterintuitive in the face of a global energy market that seems mostly in balance. The sweeping return of this potent form of coercion is dependent on a variety of trends playing out in geopolitics and in the global energy system. In view of the uncertainty surrounding these trends, more weaponization is not inevitable. But the emerging reality of great-power competition, economic fragmentation, tightening energy markets, and a greater concentration of both fossil fuels and clean energy supplies among a small number of countries increases the odds that the energy weapon will be used.

To protect their countries from the new risks, policymakers will need to summon the political courage and pragmatism to make massive new capital investments. This effort will be especially challenging given severe fiscal constraints and burgeoning debt crises in many advanced economies. Rather than rely on market forces to develop and deliver the cheapest flows of energy, policymakers will need to pursue more secure sources, even if they come at a higher cost, and build redundant and more resilient infrastructure to protect against and better handle potential energy crises. Spending at this scale will cause energy prices to rise, particularly in an era of higher capital costs. It will also lead to a more active role for the state in the energy economy, a development that will create more investment opportunities but also significantly more uncertainty for private capital. Deployed wisely, such government investments can enhance energy security and stave off the worst forms of coercion.

Counterintuitively, these very same policy responses could also provide a powerful push for clean energy. The renewed threat of weaponization means that there is more common cause between champions of a Trump-style energy dominance agenda and clean energy advocates who seek a more rapid pivot toward a less carbon-intensive economy. To be truly energy secure, particularly at a time of rapidly rising demand, the United States should invest not just in its own oil and gas sector but also in solar and wind power, batteries, electric vehicles, critical minerals, nuclear fuels, and other energy technologies, while in parallel diversifying energy supply chains. Given that oil is still priced in a volatile global market, reducing the country’s exposure to energy shocks and more overt weaponization means not just producing more but, even more important, using less.

Ultimately, the imperative to bolster energy security could be an even stronger motivator of clean energy deployment and reduced fossil fuel use than the threat of climate change itself. The coming era of weaponization could thus have a silver lining. It will create a powerful new incentive, for those concerned with energy and climate alike, to invest in the multifaceted energy and supply chain strategies that will be essential for a secure future.

Excerpts: The foreign Affairs, Published on October 21, 2025

This article has been updated to clarify that the version of the IEA’s 2025 World Energy Outlook to which it refers is a draft; at the time of publication, the final report had not yet been released.

Jason Bordoff is Founding Director of the Center on Global Energy Policy and Professor of Professional Practice at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs. During the Obama administration, he served as Senior Director for Energy and Climate Change on the staff of the National Security Council.

Meghan L. O’Sullivan is Director of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs and the Jeane Kirkpatrick Professor of the Practice of International Affairs at the Harvard Kennedy School. During the George W. Bush administration, she served as Deputy National Security Adviser for Iraq and Afghanistan.

प्रतिक्रिया