The Concept Paper is Merely a ‘Revisionist’ Interpretation of Liberal Capitalist Democracy

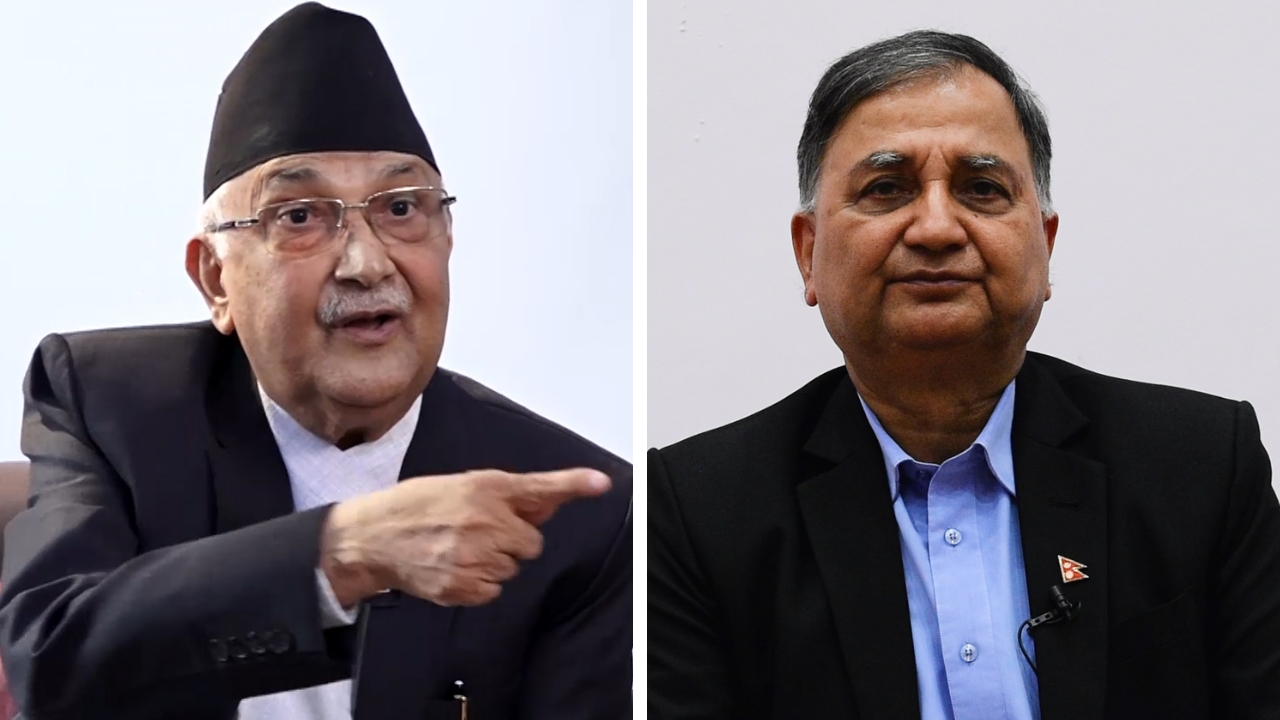

The concept paper presented by Senior Vice-Chairman Ishwor Pokhrel for the 11th National Convention of the Nepal Communist Party (Unified Marxist-Leninist) – CPN (UML) – (27–29 Mangsir 2082 / 12–14 December 2025) claims to be guided by Marxism-Leninism and People’s Multi-Party Democracy (Janatako Bahudaliya Janwad – PDP). However, there is no confusion whatsoever that this is not a revolutionary Marxist programme or policy; it is merely a different interpretation of liberal capitalist democracy. Marxism places at its centre the elimination of comprador capitalism through class struggle, the leadership of the proletariat and toiling masses, and revolutionary transition toward socialism (Marx & Engels 1848/1978).

This document, on the contrary, gives priority to reforms within capitalism itself, making the protection of private property, expansion of the market economy, and multi-party competition its main objectives. Even though it attempts to portray PDP as a “creative application” of Marxism, the theory itself is revisionist, taking an oath to abandon revolutionary struggle and remain within the capitalist framework (Lenin 1917/1964).

1. Background and Structure of the Concept Paper: Covering Up the Political Crisis

The concept paper is written against the background of the “Gen-Z” movement of 23–24 Bhadra 2082 (September 2025) and the dissolution of the House of Representatives (Pokhrel 2082, pp. 1–2). It pays tribute to martyrs and covers topics such as the global environment, analysis of Nepali society, review of the movement, democratisation of party life, etc., and does not fall behind in showing populist tendencies.

- Global situation: Crisis of capitalism and the rise of new forces (pp. 1–5)

- Nepali society: Depiction of comprador capitalism and reformist policies (pp. 6–15)

- Review of the movement: Accusations of anarchy and extremism (pp. 15–21)

- Political perspective: Solution through elections and amendments (pp. 21–24)

- Party life: Internal democracy and youth participation (pp. 24–34)

- PDP and socialism: Timely refinement (pp. 34–36)

Although this structure superficially resembles Marxist analysis, in essence it is an attempt to protect the stability of the existing capitalist system. For example, the events of 24 Bhadra(September 9) are labelled a “conspiracy” (pp. 17–18) and revolutionary possibilities are rejected, thereby weakening the Marxist concept of class struggle (Trotsky 1932/1973). The depiction of economic inequality in Nepali society is real (pp. 7–8), yet the solution is reformist – there is not even the slightest hint of a revolutionary leap, which is no surprise for the entire UML rank and file. Many things mentioned in the concept paper are superficial and suffer from a lack of evidence, resembling an amateur essay. For instance, “techno-feudalism” is mentioned (p. 2) but there is no deep analysis (Zuboff 2019). This document hides the ideological crisis of the UML; even though presented by Pokhrel, it would be more appropriate to regard it as “Oli-ite theory” (Gyawali 2020).

2. Analysis of the Global context : Acceptance of Capitalism

The document mentions the crisis of global capitalism (inequality, environmental crisis, rise of new powers) (pp. 1–5), but it does not propose any strategic line of struggle viewed through a Marxist lens; it merely suggests NGO-style methods of raising public awareness. Instead, by putting forward liberal principles such as “protection of national interest” and “relations based on equality” (p. 5), it appears as a guard of the current global liberal capitalist system. In the context of Nepal, which has become a geopolitical navel, a clear perspective should have been put forward regarding relations with China, India and the West.

The mention of inequality and migration in the “Global South” (p. 4) paints a picture of global capitalism that reveals the possibility of socialist awakening (Wallerstein 1974). The reference to the Marxist coalition in Sri Lanka (p. 5) provides regional inspiration. Yet, merely mentioning positive and negative trends of those movements in brief without clarifying what can be learned from them has no meaning.

Weaknesses: Instead of treating capitalism’s “new phase” (techno-feudalism) as a revolutionary opportunity, it shows the path of adaptation. (Techno-feudalism refers to the new practices and structures that emerge when digital technology and giant platform companies (e.g., Big Tech) turn modern economic and social relations into something resembling medieval vassalage – instead of land, they collect “rent” through control of data, cloud and platforms, and the big companies themselves become new types of “feudal overlords”. The former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis has analysed this concept in an interesting way in his book Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism. But the fact that Pokhrel gives it no more importance in his concept paper than something he heard somewhere and found attractive only exposes the low ideological level of the leaders.) On the other hand, contrary to Lenin’s theory of imperialism (Lenin 1917/1964), it treats the capitalist crisis as a precursor to revolution. The UML’s perspective has failed to rise above reformism. By making the communist movement cohabit with capitalist pluralism, the communists of Nepal who take the name of Marxism have once again placed the UML and Pokhrel himself in the front rank. Treating the victory of “New York mayor Zohran Mamdani” as a socialist signal (p. 5) is nothing but political-ideological bankruptcy. It would not be an exaggeration to say that this merely displays a revisionist character that cannot rise above news and short social-media video clips (Kshirsagar 2021).

In the historical context of the Nepali communist movement, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1990, PDP started patronising reformism and liberal capitalist democracy, turning the UML into a social-democratic party (Thapa & Sijapati 2004). In recent times, the so-called establishment faction’s claims and the street’s abuse of power have degraded the UML to a level where even the social democrats’ demand for state intervention in education and health cannot be accepted.

3. Depiction of Nepali Society: Reformist Solution to Comprador Capitalism

Describing Nepal as “comprador capitalism” (p. 6), it mentions the agricultural crisis, unemployment and climate change (pp. 8–13), yet the solutions have not risen above the same old tired prescriptions. Encouraging private investment, promoting foreign investment and the so-called modernisation of agriculture (pp. 14–15) – such things have no possibility of solving the current politico-economic crisis of Nepali society; the Gen-G rebellion itself is the vocal expression of this truth.

The analysis of migration and wildlife attacks (pp. 9–10) touches the reality of social life. Yet even this has not risen above the stale lessons of UNDP reports (UNDP 2022).

The rant about “protection of private property” (p. 14) repeats the tendency to openly reject even the state’s role in least basic sectors. This is far removed not only from Marxist theory but even from the policies taken by social democrats. The proposal to make industrialisation and job creation market-centred (p. 15) signals further promotion of Nepali capitalist development, yet in the absence of specific policies for regulation and promotion it is nothing more than beautiful rhetoric. Without a plan for just redistribution, narrowing the economic gulf in Nepali society is impossible. This tendency makes the claim of “socialism with Nepali characteristics” (p. 35) even more hollow, because even the Chinese model is regarded as capitalist reform (Harvey 2005). The self-criticism (p. 13) is superficial; it does not appear substantially different from fitting the failure of the Oli government into the “conspiracy” narrative.

Historical context: There is no sign that the UML’s economic policy, which after 2047 BS (1990 ) has continually widened class division by adopting neoliberalism, will take the path of any refinement.

4. The Gen-Z Movement: Extremism vs Democratic Reform

Labelling the movement “anarchic” (pp. 16–18), it refutes two extremisms (opposition to institutions and “everything is fine”). The solution: putting forward elections and constitutional amendment (pp. 21–24) in an attempt to appear different from Oli’s issue of restoration of parliament.

Evaluation: The emphasis on youth participation (p. 21) can address the generational gap – which is made clear by the policy that at least one delegate under 40 years of age must be mandatory in the convention delegate selection.

Labelling the Gen-Z movement a “conspiracy” (p. 18) indicates an attitude of suppressing class discontent. Treating elections as the “way out” (p. 22) makes parliamentary reform an alternative to fundamental change, which in Lenin’s words is “parliamentary cretinism” (Lenin 1902/1968). On the other hand, it has not even stopped calling the restoration of parliament a matter of judicial review in the Supreme Court (p. 23). Yet what was needed was to turn the issue into prior agreement and future parliamentary endorsement for governmental reform, change in the electoral system and strict action against corruption-related activities. This issue is being strongly raised by various analysts and Gen-Z groups as well.

The attitude of seeing the Gen-Z rebellion – which showed revolutionary potential like the 2062/63 people’s movement – merely as the fall of Oli’s ‘nationalist’ government will not lead the UML to the right destination in the days to come.

5. State of Internal Democracy

Mention of factionalism and weakness of democracy in the party (pp. 24–34), the proposal to “refine” PDP (pp. 34–35) is the main concern of the Pokhrel group.

Honestly, age limits and a two-term limit (p. 28) can bring novelty to internal party life and leadership transition. But the policy of making PDP “timely” (p. 35) mixes it with capitalist liberalism, showing that it is being dragged down rather than continuing Madan Bhandari’s PDP. The appeal for left unity (pp. 36–37) is hollow, because the failure of the UML–Maoist unity has not yet faded from memory as a spectacle of reformist enjoyment of power.

In reality, the UML’s internal democracy gave birth to Oli’s centralisation (Shrestha 2019); the Pokhrel group of the UML, which is facing such accusations, also appears to have failed to intervene appropriately.

6. Possible Conclusion

This concept paper, like Oli, also claims to make the party a “national decisive force” (p. 37), but it has completely lost revolutionary energy. It appears incapable of even refining reformist agendas in the upcoming elections. Moreover, some of the programmatic slogans mentioned in the concept paper prove the proverb “old liquor in a new bottle”:

- “Personal property will be secured to encourage commercial investment.” (What is the meaning of this rant? This is already guaranteed by the constitution. The hidden meaning of saying this must be that the UML should not be understood by the general voters as a socialist party.)

- “Rule of law will be strictly implemented. Necessary steps will be taken to free the civil service and police from party pressure and make them service-oriented and professional.” (This naturally means that until now they were partisanised and will now be abandoned.)

- “The unholy relationship between existing politics, administration and businessmen – which makes policy on the basis of commission and nourishes cronies – will be prohibited and an environment of clean competition will be created.” (This is the very reason the Gen-Z rebellion had to strike at everyone’s navel. Then without a programmatic and phased programme of how this will be reformed, why should voters believe it?)

- “Jobs will be created through industrialisation, farmers will be linked to the value chain by establishing agro-processing industries, employment-oriented vocational education will be emphasised from school level, and by encouraging innovative creativity youth will be made self-employed and the environment created for them to stay in the country.” (This is rhetoric expressed in the desire of the general public. But the perspective of a political party should be able to say concretely: to solve these problems we will do this and this. Here the Pokhrel group has given no signal of any change in the UML policy of handing education over to the private sector and running the party from them.)

- “Agriculture will be fully modernised and farmers will be encouraged to move from subsistence farming to modern farming. Necessary arrangements will be made to reduce the production cost of small and medium farmers and ensure minimum profit.” (Whenever the UML has announced policy programmes and budgets on behalf of the government since 2051 BS, were such things ever missing? If so, why were they not implemented? And how will people believe in the coming days just because it is written?)

- “Effective policies will be made and implemented to resolve the existing structural crisis in the economy through development of industry, tourism, energy, agriculture and infrastructure.” (This is merely a ritual phrase; without phased determination of infrastructure to modality and targets in energy and tourism it can be nothing more than populist slogans.)

- “Investment coming from non-resident Nepalis will be encouraged and existing provisions regarding reinvestment and profit repatriation will be further facilitated. In addition, policy and legal arrangements necessary for them to come to Nepal, live and do business will be made easier so that their knowledge, skill and experience can be used for the benefit of the country.” (The party that has been the most illiberal about giving them voting rights saying this is nothing but hypocrisy.)

- “Necessary policy arrangements will be made so that social justice is reflected in the distribution of benefits that will come after increasing the economic growth rate. The role of the state will be gradually increased in the fields of education, health, public transport and security of the disabled, helpless, senior citizens and helpless citizens.” (The UML’s policy has been insistent on shrinking state policy in such areas. There is no possibility that the general public will believe how this will now change.)

The above attitude is certain to invite class rebellion. Even the opinions publicly expressed by the leaders of the group about strengthening the party’s internal democracy remain silent in the concept paper, expressing only fear of Oli. Based on this concept paper, the role that the leaders of this group will play in the coming party life and what their role will be even after the party’s defeat in the election will determine the future of both them and the UML party. Ultimately, just as Chairman KP Sharma Oli thinks – that the UML is Oli and Oli is the UML – there is no room to rise above the 11th Convention. Moreover, the fact that the Pokhrel group has made the renewal of party membership of former President and Madan Bhandari’s wife Bidya Devi Bhandari one of its main agendas makes it seem as if, as Oli said, the existence of this group is only to appease Bhandari.

References:

Bhattachan, K. B. (2018). The Nepali state and ethnic rights: A critique. Kathmandu: Central Department of Sociology, Tribhuvan University.

Gyawali, D. (2020). Water, conflict, and cooperation: Lessons from Nepal. In Water resources management in South Asia (pp. 123-145). Springer.

Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford University Press.

Hobsbawm, E. J. (1994). The age of extremes: A history of the world, 1914-1991. Pantheon Books.

Huitzinga, A. (2005). The Maoist insurgency in Nepal. Small Wars & Insurgencies, 16(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592310500034804

Jha, H. B. (2013). The Nepali Congress and the communist parties in Nepal. In The politics of change in Nepal (pp. 56-78). Adroit Publishers.

Kshirsagar, A. (2021). The rise of democratic socialists in the US: DSA’s challenges. Journal of American Politics, 45(2), 210-225.

Lenin, V. I. (1964). Imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism(Original work published 1917). Progress Publishers. (Original work published 1917)

Lenin, V. I. (1968). What is to be done? (Original work published 1902). Progress Publishers.

Marx, K. (1976). Capital: A critique of political economy (Vol. 1) (Original work published 1867). Penguin Books.

Marx, K., & Engels, F. (1978). The communist manifesto (Original work published 1848). Penguin Books.

Muni, S. D. (2016). Nepal’s transition: Politics and security challenges. Strategic Analysis, 40(3), 189-202. https://doi.org/10.1080/09700161.2016.1184184

Ogura, K. (2007). Maoists, the party, and the army. In Understanding the Maoist movement in Nepal (pp. 45-67). Martin Chautari.

Pandey, R. N. (2013). Nepal’s political parties and their ideologies. Kathmandu: Pairavi Prakashan.

Pokhrel, I. (2082). Nepal Communist Party (UML) 11th National Congress: Concept paper. Nepal Communist Party (UML). (Original work in Nepali)

Shrestha, K. (2019). Internal democracy in Nepali political parties. Nepal Journal of Political Science, 12(1), 34-50.

Thapa, M., & Sijapati, B. (2004). Revolution and democracy in Nepal. Kathmandu: Himal Books.

Trotsky, L. (1973). The revolution betrayed (Original work published 1932). Pathfinder Press.

UNDP. (2022). Human development report 2022: Uncertain times, unsettled lives. United Nations Development Programme.

Wallerstein, I. (1974). The modern world-system I: Capitalist agriculture and the origins of the European world-economy in the sixteenth century. Academic Press.

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism. PublicAffairs.

प्रतिक्रिया