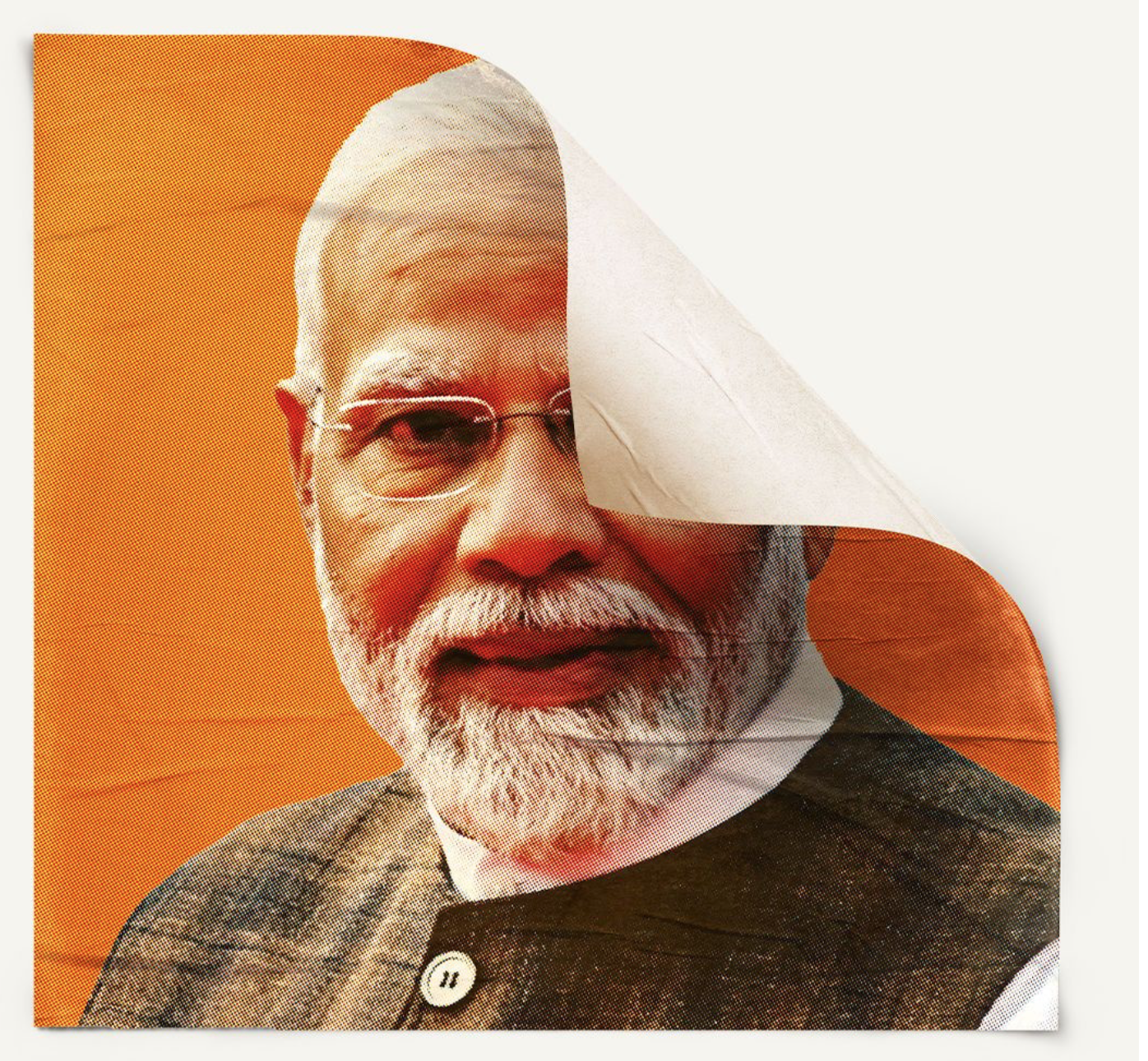

The shock election result will change the country—ultimately for the better

The world’s biggest electorate has just shown how democracy can rebuke out-of-touch political elites, limit the concentration of power and change a country’s destiny. After a decade in charge, Narendra Modi was forecast to win a landslide victory in this year’s election; yet on June 4th it became clear that his party had lost its parliamentary majority, forcing him to rule through a coalition. The result partially derails the Modi project to remake India. It will also make politics messier, which has spooked financial markets. And yet it promises to change India for the better. This outcome lowers the risk of it sliding towards autocracy, buttresses it as a pillar of democracy and, if Mr Modi is willing to adapt, opens a new path to reforms that can sustain its rapid development.

Related international media coverage on Indian Election Results:

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/05/world/asia/india-election-modi.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/04/world/asia/india-election-2024-takeaways.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/05/world/asia/india-elections-modi-coalition.html

https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/jun/06/first-edition-india-election-modi-future

The drama unfolding amid a scorching heatwave begins with the election results. Mr Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (bjp) aimed to take up to 370 seats in the 543-member lower house, an even bigger majority than in 2014 or 2019. Instead it won just 240. It lost seats to regional parties in its heartlands in Uttar Pradesh and beyond, reflecting a revival of caste-based politics and, it seems, worries about a lack of jobs. Whereas his coalition partners were previously optional extras, he will now rely on them to stay in power. Their loyalty is not guaranteed.

This is not just an electoral upset, but a repudiation of Mr Modi’s doctrine of how to wield power in India. As our new podcast The Modi Raj explains, he is a remarkable man, born in poverty, schooled in Hindu-first ideology and consumed by the conviction that he was destined to restore India’s greatness. For Mr Modi, India has been kept down by centuries of rule under Islamic dynasties and British imperialists, followed after independence by socialism and the chaos inherent in diversity and federalism.

For over a decade Mr Modi’s answer has been to concentrate power. That meant winning elections decisively on a platform that emphasises his own brand, Hindu chauvinism and an aspirational message of rising prosperity. In office, his method has been to use executive might to ram through policies that boost growth and reinforce the bjp’s grip on power.

Mr Modi has changed India for good and ill. Fast growth promises to make its economy the world’s third-largest by 2027. India has better infrastructure, a new digital welfare system for the poor and growing geopolitical clout. However, good jobs are too scarce, Muslims suffer discrimination and, under a sinister illiberalism, the bjp has captured institutions and persecuted the media and opposition.

This year’s election was supposed to mark the next phase of the Modi Raj. With an even larger majority and a new presence in the richer south of the country, the bjp aspired to unitary authority across India at the central and state level. That might have made big-bang reforms easier in, say, agriculture. But such power also raised the threat of autocracy. Many in the bjp hoped to forge a single national identity, based on Hinduism and the Hindi language, and to change India’s liberal constitution, which they view as an effete Western construct.

Mr Modi would have reigned supreme. Yet every Raj comes to an end. If, as expected, the bjp and its allies form the next government, Mr Modi will have to chair a cabinet that contains other parties and which faces parliamentary scrutiny. That will come as a shock to a man who has always acted as a chief executive with unchallenged authority to take the big decisions. Succession will be debated, especially inside the bjp. Even if Mr Modi completes a full term, a fourth one is now less likely.

Mr Modi’s diminished stature brings dangers. He could resort to Muslim-bashing, as in the past. That would alienate many Indians but might possibly repair his authority with his base and the bjp. Coalition government makes forcing through economic changes harder. The small parties may gum up decision-making as they demand a share of the spoils. India’s growth is unlikely to fall below its underlying rate of 6-7%, but higher welfare spending may lead to cuts in vital investment. That explains why the stockmarket initially fell by 6%.

These dangers are real, but they are outweighed by the election’s promises. Now that the opposition has been revived, India is less likely to become an autocracy. The bjp and its allies also lack the two-thirds majority they needed to make many constitutional changes. Disappointed investors should remember that most of the value of their assets lies beyond the next five years and that the danger posed by democratic backsliding was not just to Indians’ liberty. If strongman rule degenerated into the arbitrary exercise of power, it would eventually destroy the property rights that they depend on.

More open politics also promises to boost growth in the 2030s and beyond. The election shows that Indians are united by a desire for development, not their Hindu identity. Solving India’s huge problems, including too few good jobs, requires faster urbanisation and industrialisation, which in turn depend on an overhaul of agriculture, education, internal migration and energy policy. Because the constitution splits responsibility for most of these areas between the central government and the states, the centralisation of the past decade may yield diminishing returns. The next set of reforms will therefore require consensus. There are precedents. Two of Mr Modi’s main achievements, tax reform and digital welfare, are cross-party ideas that began under previous governments. India has had reforming coalitions before, including bjp-led ones.

Modi modified

The question facing India is therefore whether Mr Modi can evolve from a polarising strongman into a unifying consensus-builder. By doing so, he would ensure that India’s government was stable—and he would usher in a new sort of Indian politics, capable of bringing about the reforms needed to ensure India’s transformation can continue when the Modi Raj is over. That is what real greatness would look like, for Mr Modi and his country. Fortunately, if he fails, India’s democracy is more than capable of holding him to account. ■

Excerpts: The economist, June 5, 2024

COMMENTS